Hope & Health

Articles and Updates from WVU Medicine Golisano Children's

09/3/2024 | P. David Adelson, MD

Chiari Malformation: Understanding the Basics

Chiari malformations are a fairly common problem and occurs when a part of the brain extends through an opening where the skull meets the spinal canal. It can happen if the skull is too small or misshapen but even in normal skulls. Chiari malformations are estimated to occur in 1 in 1000 births and with a slight female predominance (3:1 ratio of females to males).

In Chiari malformation, the structural abnormality is when the cerebellum — the part of the brain responsible for balance and coordination — extends below the skull into the spinal canal. This condition affects the flow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and can lead to various symptoms due to blockage of fluid or pressure on the brainstem and or spinal cord.

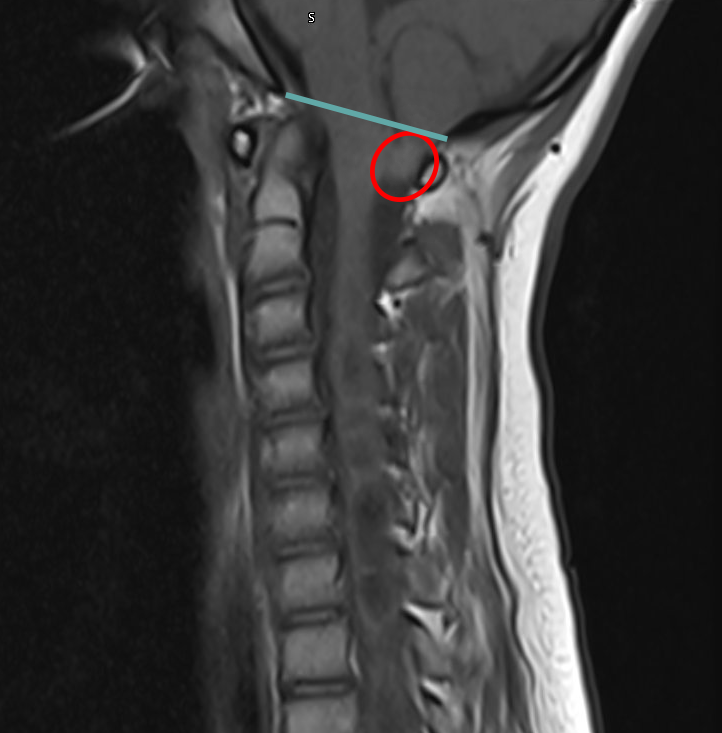

The straight line represents the base of the skull. The red circle indicates where part of the brain has extended into the opening where the skull meets the spinal canal.

The straight line represents the base of the skull. The red circle indicates where part of the brain has extended into the opening where the skull meets the spinal canal.

There are several types of Chiari malformation, but the most common one seen most often is Chiari I Malformation (CM-I). In CM-I, only the cerebellar tonsils extend below the foramen magnum (the opening at the base of the skull). It’s often asymptomatic and can be found “incidentially” if imaging is obtained for another reason (i.e.) concussion. CM can cause problems and seen most often associated with headaches, neck pain, vomiting and or other issues.

Other types of CM occur but other typically associated with other issues such as myelomeningocele (a form of spina bifida), prenatal malformation that is incompatible with life, or extremely rare, when the cerebellum does not develop normally.

Signs and symptoms

The symptoms of Chiari malformation can vary widely and are often non-specific. The common ones include:

- Headaches: Persistent headaches, especially at the back of the head or neck.

- Neck Pain: Chronic neck pain or stiffness.

- Balance and coordination issues: Problems with walking, clumsiness, and dizziness.

- Weakness and numbness: Weakness in the arms or legs, tingling, or numbness.

- Swallowing difficulties: Trouble swallowing or choking.

- Vision problems: Blurred vision, double vision, or other visual disturbances.

Because these symptoms can occur with other brain issues, CM can be misdiagnosed or underdiagnosed. Further investigation and imaging should be done if:

- Headaches are unresponsive to medications and keep being diagnosed as “migraines”

- Vomiting not due to GI problems and associated with the headaches

- Balance issues are persistent following a concussion

- Complaints of numbness and tingling in arms and fingers continue even when up and trying to “shake it out.” This is often misinterpreted as sleeping on the arm “funny” • Double vision not easily recognized and no other issues • Face weakness sometimes misdiagnosed as “Bell’s Palsy”

How do we make the diagnosis of CM?

The best way to diagnose a CM is through imaging. The imaging modalities most often used include:

- MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging): This imaging technique provides detailed images of the brain and spinal cord to see extent of cerebellar compression, fluid blockage and any cyst/ syrinx formation in the spinal cord.

- CT (Computed Tomography) scan: Sometimes used to assess bony abnormalities as well as often obtained after a concussion and the CM can be seen incidentally

Treatment options

- Observation: Most asymptomatic cases found incidentally or those with only mild symptoms may only require regular monitoring.

-

Medication:

- Pain relief: Over-the-counter pain relievers (e.g., ibuprofen) can help manage headaches.

- Anti-nausea medications: Useful for associated symptoms.

Indications for surgery

Not everyone with a Chiari malformation requires surgery but depends on a patient’s individual circumstances. These may include 2 specific indications:

- Symptoms not responding to conservative treatment and interfering with the patient’s quality of life.

- Presence of syringomyelia (fluid-filled cyst within the spinal cord).

Understanding syrinx and syringomyelia

A syrinx is a fluid-filled cyst that forms within the spinal cord and a patient has syringomyelia if they have a cyst in the spinal cord not due to tumor or other obstruction in the spinal cord itself but due to a congenital anomaly such as a CM or tethered cord/ spinal bifida. It occurs because of obstruction of the fluid outflow due to obstruction. Because it can grow larger over time, damaging the spinal cord and causing pain, weakness, and stiffness, and that damage is often permanent and irreversible, surgery is often recommended in these circumstances due to concern for long term damage.

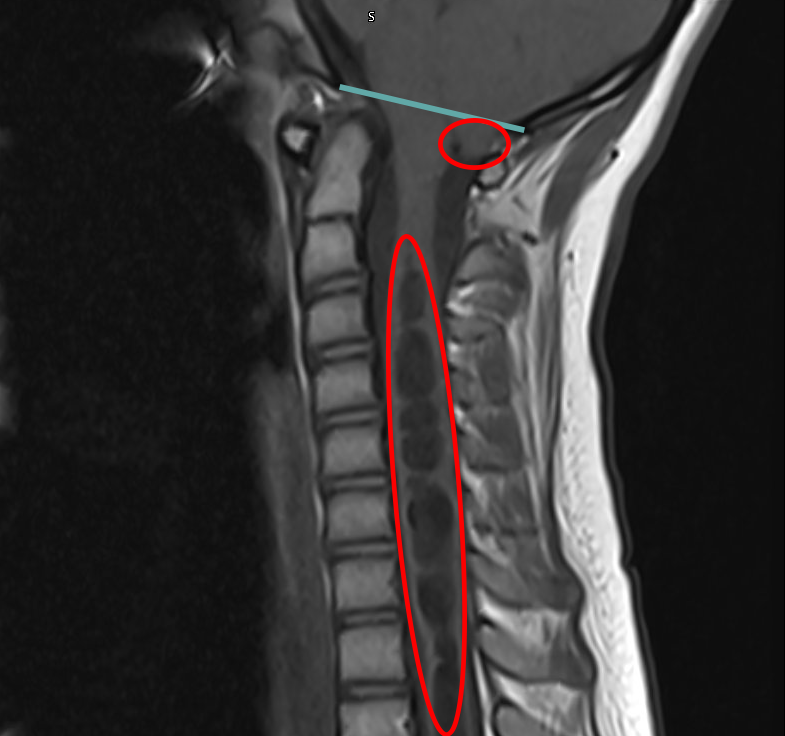

Again, the straight line represents the base of the skull. And again, the smaller red circle indicates the Chiari malformation - where part of the brain has extended into the opening where the skull meets the spinal canal. The Chiari malformation is acting like a dam and created a syrinx - a fluid filled cyst within the spinal cord (long red circle).

Again, the straight line represents the base of the skull. And again, the smaller red circle indicates the Chiari malformation - where part of the brain has extended into the opening where the skull meets the spinal canal. The Chiari malformation is acting like a dam and created a syrinx - a fluid filled cyst within the spinal cord (long red circle).

Surgery for treating CM

If warranted, a neurosurgeon may recommend a Chiari decompression surgery (known as a “decompressive suboccipital craniectomy and cervical laminectomy”. The goal of surgically treating CM is to reduce or eliminate the pressure on the spinal cord caused by the cerebellar tonsils and or alleviate the obstruction of the CSF flow.

Under general anesthesia and while completely asleep, an incision is made in the back of the head and the neurosurgeon removes a small piece of bone at the base of the skull to widen the outflow area for the CSF. If enough pressure has been relieved with the removal of bone only, then the incision is closed. If further decompression is necessary, the covering of the brain and spinal cord, the dura, is opened and results in further and more broad reduction of pressure on the spinal cord. In some instances, the cerebellar tonsils are coagulated back using an electrocautery to make further room and ensure CSF outflow. When the dura is opened, an expansile duraplasty is performed which involves patching the dura (the protective covering around the brain) to reconstruct the covering but also expand the space in this area to leave room to improve CSF flow.

In rare instances, the patient may develop or had underlying hydrocephalus (excess CSF buildup in the brain). The treatment involves either a ventriculoperitoneal shunt where a tube drains excess CSF into the chest or abdomen or a third ventriculostomy is performed with an endoscope to create a small hole in a brain cavity to release trapped CSF and create an alternative pathway.

Short-term and long-term outcomes

After surgery, patients often experience headaches and neck pain due to the surgery but soon as they heal, they feel relief and that their headaches are different and get better. In the long term, some individuals may need ongoing management but most times, they become symptom-free and return to their usual activities and even more. Regular follow-ups are crucial and following up imaging is obtained if their was an underlying syringomyelia or hydrocephalus.

Living with Chiari malformation

Most important in self-care in dealing with CM is to manage stress, maintain good posture, and avoid activities that strain the neck. Some patients and families find help and support with Chiari Support Groups. Connecting with others who have CM can often, provide emotional support and know that they are not alone out there.

Remember, every case is unique, and personalized care is essential. Consult a healthcare professional for accurate diagnosis and treatment recommendations. If you have questions or concerns about whether you have a CM or some other neurological diagnosis, please contact us at the WVU Medicine Children’s Neuroscience Center.

Sources